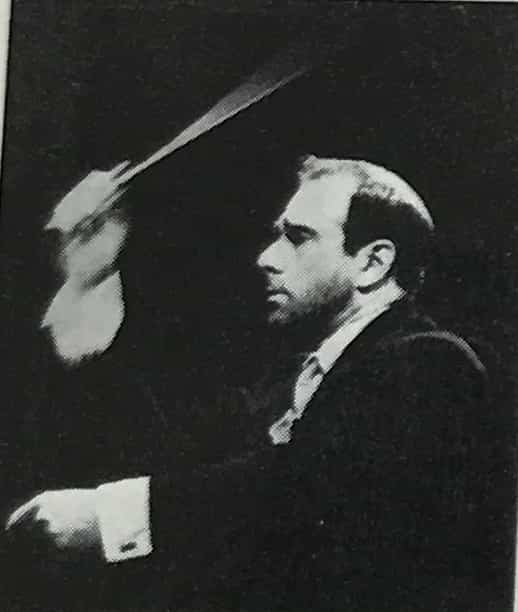

George Hurst was renowned for a remarkable conducting technique, which was clear, focussed, expressive and fluid. He was able to transmit his musical intentions directly and unambiguously to an orchestra, and was therefore capable of achieving excellent performances on limited rehearsal time (a factor which made him an ideal conductor for the frequent radio broadcasts of the BBC Northern, although in later years he would often demand more rehearsal time than usual).

His feeling for orchestral sound, shown in his baton technique, had the ability to transform almost any orchestra he worked with. His signature sound changed somewhat during the course of his career: early recordings with the Royal Danish Orchestra present a very clean, lithe, well-articulated sound, with great clarity; later work demonstrates a weighty, bass-driven, warm and powerful sound – thrilling in its effect and absolutely unmistakable to listen to.

He learned his technique from Leon Barzin in New York. Barzin, an excellent conductor in his own right, had played viola in the NBC orchestra for many years, and codified the technique of Arturo Toscanini. Barzin described the technique as follows:

“Co-ordination means absolute control from the tip of the toe to the very end of the stick, so that no motion of any part of the body may confuse the musical content of the score. A definite sign of a conductor’s lack of co-ordination is his need to explain all his meanings through speech rather than through his stick during rehearsal periods.

There is no question that a certain amount of speech is needed. But if you talk to your violin all day it will not play the passage for you. You must create the sound, the precision, the interpretation. So should the baton. It saves a great deal of time. The average orchestral musician is a sensitive human being, who reacts to the slightest motion, even that of a muscle, if it is intended to convey a musical message.”

The resulting ‘Toscanini-Barzin’ technique formed the main basis of Hurst’s conducting style, although much of it evolved into his own distinctive language. This technique was taught to generations of conductors from across the globe at the Canford (now Sherborne) Summer School of Music from 1959 until his death. It also provided the basis of courses at the Royal Academy of Music, where one of his pupils, Colin Metters, developed a world-renowned postgraduate course as Head of Conducting, and is now Professor Emeritus in Conducting. Another former pupil, Denise Ham, in turn codified Hurst’s technique and is the foremost authority on this style and a widely respected teacher of conducting. Having formerly been in charge of undergraduate conducting tuition at the RAM, she established this technique as the main basis of teaching at that institution and this work has been continued by her successors and by her at London Conducting Academy. A full, visual, analysis of his technique is provided in her successful teaching video, ‘The Craft of Conducting’.

Essential Elements of Hurst’s Technique

‘Focal point conducting’

The position of the baton in the hand, the hold of the baton and its relation to the rest of the body, results in the point of the stick remaining the focus at all times which, in turn is always connected to the eyes. Even with larger gestures the placing of the sound is always within the area of the diaphragm with relation to a central point in the middle of the sternum. The beating usually remains within an imaginary ‘frame’ around the upper body so that players never have to ‘search’ for the beat or try to guess the conductor’s intention through facial expression alone. Movement is initiated from the upper arm and maintains direct contact with the breathing whilst the elbow, forearm, wrist and fingers, work in proportion to each other in order to transmit the required articulation to the point of the baton. Ilya Musin, the great Russian teacher of conducting, described conducting as ‘breathing with your arms’, while Barzin talked of ‘the singing stick’. The technique can be compared to that of a singer or wind player: the breath through the upper arm continually ‘supports’ the sound whilst the smaller units of the forearm, wrist and fingers (‘tongue & teeth’) supply the articulation. The position of the baton within the conducting ‘frame’, the nature of the grip and the angle of the stick can all change, depending on the required sonority, and often reflect differences in texture and register within the music. The basic stance is grounded and upright but flexible – never ‘walking’ around the rostrum but with the upper body and hips free to move in a way that ‘frames’ the baton and reinforces the character of the music. Feet are usually hip-width apart – although, again, this may change depending on the nature of the music being conducted. The overall appearance is one of complete integration of body, baton, left hand and eyes, with no extraneous movement and nothing to distract.

The ‘legato’ beat

He would initially teach a legato beat in order to emphasise the importance of connection and transfer of sound between beats; this, together with the breathing, is where control of the sound originates. The sense of breathing and ‘space between the beats’ is never lost, even in faster and more articulated music, when additional clarity is achieved by increased use of the wrist and fingers. There is rarely any physical tension no matter how large or forceful the movements; so a fortissimo results from collecting and releasing the sound from the breath, never ‘hitting’.

An essential feature of the sound he was able to draw from an orchestra was a warm, singing legato. This was influenced by a ‘signature’ broad sweep of the baton across the body, similar to a violinist’s use of the bow. This would flow seamlessly ‘across’ the sound, maintaining continual ‘contact’ from the string section – he talked continually to pupils about ‘identifying with the playing’. The ‘ictus’ point of the beat would be subsumed within this broad sweep, emphasising the larger span of a phrase and reducing the artificial constraint of the barline.

Positions of the Baton

This aspect of technique, taught rigorously by Barzin, relates to subtle changes in the basic hold and angle of the baton to reflect changes of texture in the music. These subtle changes are discussed and illustrated in ‘Craft of Conducting’ Volume II.

‘Repertoire’ of gesture

He often referred to the need for a ‘repertoire of gestures’ and himself employed a wide gestural language in order to communicate musical intention with the utmost clarity. A central aim would be to contain (as far as possible) as many crucial rhythmic, textural/articulation and dynamic elements of a score, within the beating. He would often refer to use of ‘natural gestures’ within conducting, such as those that might accompany everyday speech — this was of particular relevance with regard to use of the left hand. Independence of the left hand was a vital element of the technique: how to use it to amplify, if necessary, what is already being shown in the beating and to convey something specific rather than it being continually in motion – never as a mere ‘cueing device’.

Breathing and Integration with the Body

The most crucial aspect of Hurst’s technical outlook (and, indeed, the basis of all effective conducting) is the fundamental connection of the beating with breathing, without which there is no real control. Furthermore, the entire body is involved in supporting movements of the arms and the baton, especially where larger gestures are employed. He often said to pupils that the conductor should ‘look like’ the music – another way of reiterating Barzin:

“Co-ordination means absolute control from the tip of the toe to the very end of the stick, so that no motion of any part of the body may confuse the musical content of the score”

Economy of movement

His technique was notable for the absence of extraneous, histrionic or flamboyant movements, illustrating his own advice to pupils:

“There are only two things that matter when you conduct – the music and the people who play it — in that order”