‘The Composer’s Advocate’

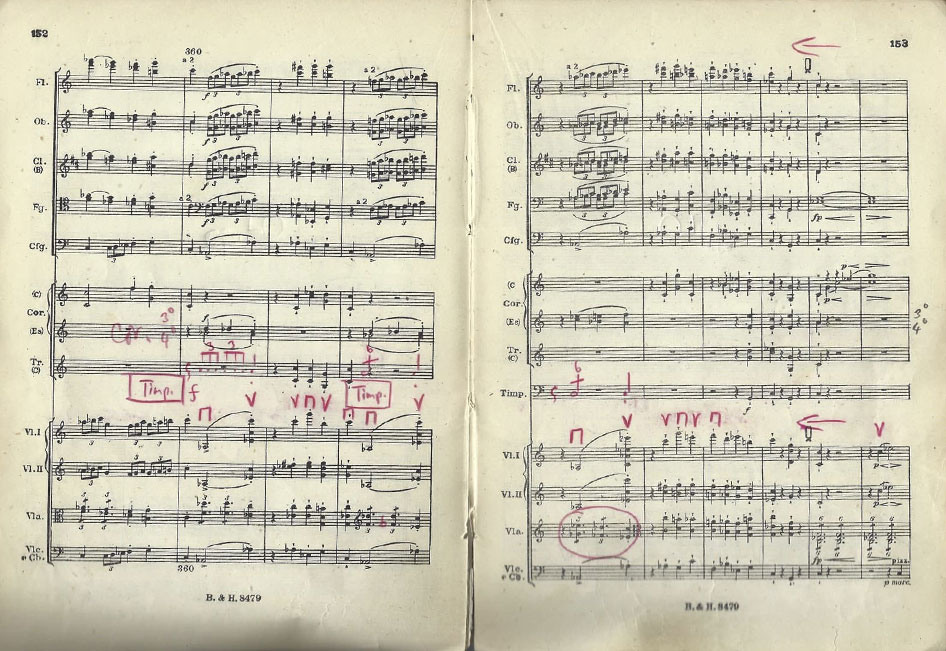

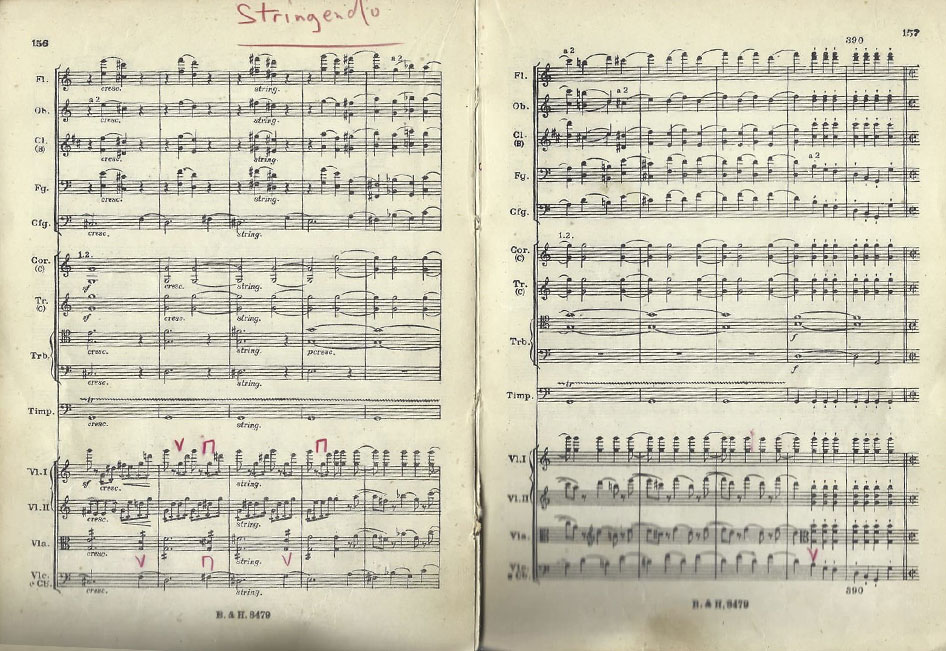

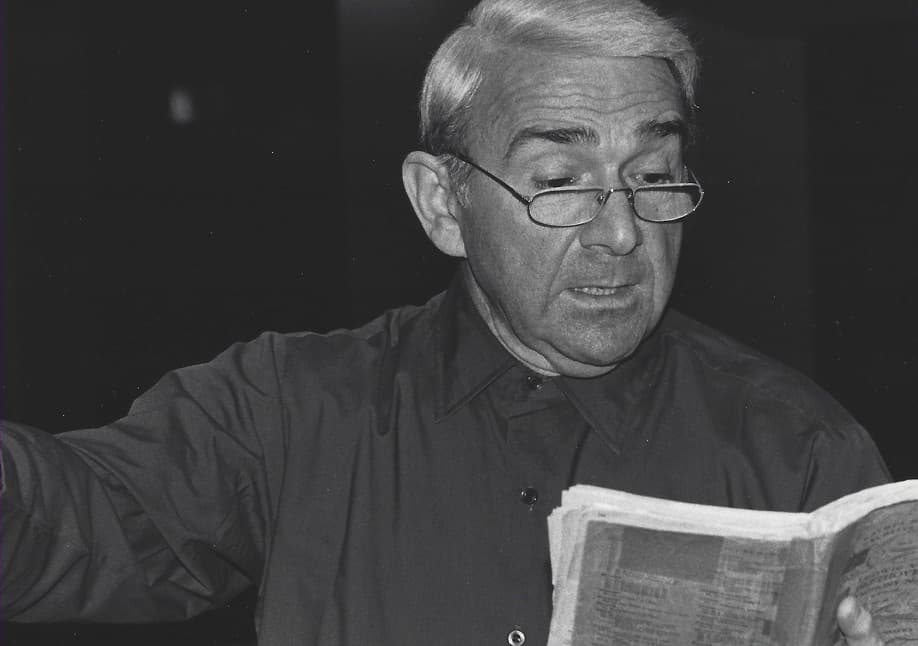

Before he ever thought of conducting George Hurst was a composer and pianist, and it is this combination of composer and performer that underpins his musical approach. As a composer he was well aware of the limits of notation and was fond of quoting Mahler: “Everything is in the score, except that which is most important.”

He constantly strove to discern the composer’s intention from the printed score but combined this with an artist’s imagination — “one must hear the composer thinking.” (GH)

There was never an ‘academic’ detached feeling — always complete emotional involvement but never at the expense of symphonic structure and always with a sense of performance.

Tempo & Structure

- Tempo is inextricably linked with symphonic structure so that one thing naturally leads to another. “Never think of tempo, think of the music and the tempo will be right.” (GH)

- The employment of subtle tempo rubato: what Beethoven called ‘gefühlstempo’ (tempo of feeling) — often described by George Hurst as simply allowing every phrase to have its own nature, affecting, in subtle ways, the tempo.

He considered that performances of the Beethoven symphonies, for instance, often adopted one of two extremes: taking the metronome mark with no variation throughout a movement, or ignoring it altogether. He considered that the metronome mark gave a clear indication of the composer’s thinking and the basic tempo of a movement, but not at the expense of the music having space to breathe.

As the composer Carl Maria von Weber put it:

“Time must not be a tyrannical millstone which sometimes pushes you forward and sometimes holds you back. It must be to music what the pulse is to the human being.

“There is no slow tempo which does not demand in certain passages a faster speed to avoid exaggeration. There is no Presto, on the other hand, which does not demand a slower treatment of certain passages in order not to jeopardise expression by rushing…changing of tempo can only be effected in the musical-poetical sense over whole sections and phrases, in complete keeping with the passion of the expression. There is no way for a composer to mark this in music.”

Gunther Schuller, in his book ‘The Compleat Conductor’ expounds this clearly:

“The lesson to be drawn from Wagner’s writing on tempo rubato in ‘On Conducting’ is that a composer’s score must be inherently respected in all its details; that such fidelity to the score ought not necessarily to result in stiff, accurate-to-the letter, rigidly metronomic renditions, but can instead, as dictated by the spirit and feeling of the music, incorporate the concept of a flexible tempo, of subtle inflections and nuances; and that such tempo variations ought never to go beyond the bounds of the basic tempo, ought never to lead to distortions and exaggerations of tempo.”

Gunther Schuller, ‘The Compleat Conductor’, p 85

- An unerring sense of direction, so that a symphonic piece or movement becomes one line from start to finish, whilst incorporating small fluctuations of tempo.

- Adherence to the composer’s tempo markings within a movement but integrating them, so that “it doesn’t sound as if you are reading a road map” (GH). The markings are often a description of what the music naturally does rather than an instruction.

- A repeated passage at the end of an Allegro movement would often be taken a notch faster to emphasise the sense of direction and his dictum that “nothing is ever the same twice”.

- His fluent technique made it possible to – as he put it – ‘play the orchestra’ with the same freedom as an instrumentalist and yet always give the players what they needed.

In an oft-repeated phrase to his pupils:

“There are only two things that matter when you conduct – the music and the people who play it — in that order!”

Dynamics

- His approach to these is revealed in advice given to pupils:

‘Dynamics are not there merely to be heard but to be felt’

‘Without dynamics you have a musical corpse’

‘Don’t be afraid to go too far to get at the meaning’

Dynamics were never a question of decibels, but a proportional element in the meaning and dramatic story of the music, and inextricably bound up with breathing and placing of phrases.

He was insistent on the difference being felt between forte and fortissimo — particularly in Beethoven. Likewise between piano and pianissimo — piano always to be more generous before a pianissimo (“pianissimo should sound like a different world” – GH) or when preceded by forte — “after a forte, piano can always be more or it sounds like forte subito nothing”.

Orchestral Balance and Sonority

- He saw one of the conductor’s most important jobs in rehearsal as being “to get the noise out of the music”. In his performances and his teaching George would go to extraordinary lengths to ensure that the audience “heard the tune”. He would make sure the tune was heard “at all costs and regardless of how many fortes are in the score” (GH) so that the line—the tune—no matter where in the orchestra, was always clearly heard.

His rehearsal method, rather than simply marking parts or issuing instructions to ‘play softer’, was most often to make sure the players heard what they had to accompany.

- A hallmark of his performances was a richness of orchestral sonority and refined quality of sound. This was achieved by various means, including encouraging lower octaves, attention to length of notes, and what he called “filling the bar” with sound.

His whole physical approach contributed to this as much as anything. The beating was crystal clear but utterly musical and free, never ‘hitting’ and inducing a bad sound, no matter how strong the dynamic. His technique, impeccable and helpful to the players, was always at the service of the music.

Phrasing

- His technique allowed him to ‘play the orchestra’ (GH) and to shape a phrase with the same freedom and spontaneity that an instrumentalist would employ. However, he spoke often about ‘accompanying the orchestra’ — giving the players space to breathe and shape a phrase, particularly wind soloists.

- He continually begged conductors and players to “take care of last notes”. They are so often played carelessly and “swallowed” or shortened in an effort to prepare the next phrase.

- A fashion has developed in the classical repertoire for “tailing off” forte phrases with a diminuendo, particularly before a silence and an ensuing piano phrase. The result of this is the killing of two birds with one stone — to “castrate” (GH) the forte phrase and to rob the piano phrase of its contrasting effect in a misplaced effort at “good taste”. George would have none of this “castrated music-making”, being unapologetic in finishing a phrase forte if that is what was marked.

- Stresses were removed from the barline, unless indicated by the composer. Inadvertent accents — sometimes an accident of the bow — did not interrupt the direction of a phrase. The players always knew where they were in the bar but his technique was never characterised by ‘beating’ so that the music was free to sing. He had a natural sense of singing and dancing, saying “all music is one or the other, often both”.

- A sudden change of character in a new phrase was achieved by ‘placing’ the new phrase with a momentary breath before it, as an instrumentalist would. This also gave the players time to prepare with bows & breath, with the resultant improvement in the sound. An oft-repeated phrase to pupils was “what’s good for the music is good for the playing”.

Articulation

- The dot! His attention to length of notes and sound was greatly at odds with the habit of playing short as soon as a dot appears over or under a note.

His approach is clearly expressed by Erich Leinsdorf in his book, ‘The Composer’s Advocate’:

“Because of rigid and unimaginative teaching, most people believe that this ‘staccato’ sign means simply that a note is to be played as short as possible. Nothing could be further from the truth. No greater diversity can be found in music than in the possible interpretations of this little mark…’staccato’ simply means ‘detached’. It was first used to indicate that notes should be separately articulated rather than tied together.”

Leinsdorf makes particular reference to the scherzo of the ‘Eroica’ Symphony:

“It is significant that on the first page of the scherzo the word ‘staccato’ is spelled out twice, as if the dots themselves might not be a sufficient signal to the players to make the notes very short…we should suspect that, even in Beethoven’s time, dots over notes did not necessarily imply extreme shortness.“

As a composer himself, George Hurst was acutely aware of the limits of notation, of the need for imagination, and for looking ‘underneath the notes’ on the part of the conductor, whilst paying acute attention to what the composer, in an effort to convey their intention, has written.

His approach to the score was communicated to pupils in two oft-heard phrases:

“Don’t look at the score, let it look at you!” (GH) — in other words, don’t come with preconceptions but see what is there and try to find the meaning.

Rhythm

- His own sense of rhythm was impeccable, and pupils were often exhorted to employ more “rhythmic grip”, particularly in fast passages. This came not from the arms but from the breath.

Again, an oft-heard phrase:

“Music sounds faster and more exciting if you can hear all the notes”.